Lonnie Thompson and his colleagues go to great trouble to extract ice cores like this from remote glaciers to learn the secrets they store about the earth’s past.

By Richard Ades

One admirer compares research scientist Lonnie Thompson to Indiana Jones. Another compares him to Clark Kent, the deceptively average-looking individual who is, in reality, Superman.

Both comparisons are apt, as we learn from Canary, a documentary directed by Danny O’Malley and Alex Rivest. The film details Thompson’s decades-long effort to uncover the history stored in glaciers found in some of the world’s highest and least-accessible locations. It also explains how the Ohio State professor became a major voice in the fight against climate change.

Even before the opening credits appear, we’re shown an incident in a war-torn area of Indonesia that encapsulates Thompson’s bravery and commitment to the environment.

After demanding to meet with him, members of a local tribe ask why he and his team are drilling into a mountaintop glacier that they consider the head of their god. Is he trying to steal the deity’s memory? Thompson tells them that’s exactly what he’s doing, because the glacier that stores the “memory” is in danger of melting away.

Serving as the film’s narrator along with other experts such as his wife, Ellen Mosley-Thompson—a glaciologist in her own right—Thompson explains that glaciers are like the canary in the coal mine. In the olden days, caged canaries were taken into mines to serve as early warning systems. If the air got too thin to keep the tiny birds alive, miners knew they had to leave quickly or suffer the same fate.

Thompson’s point is that glaciers have served the same function. By melting and shrinking, sometimes with shocking speed, they’ve offered some of the earliest evidence that the climate is changing and we’d better do something about it or suffer the consequences.

The analogy comes naturally to Thompson, as he was born and raised in a poor area of West Virginia that’s dominated by the coal industry. Ironically, considering the role fossil fuels have played in climate change, he originally enrolled at OSU to study coal geology. However, he eagerly switched fields when he was offered a job studying glaciers.

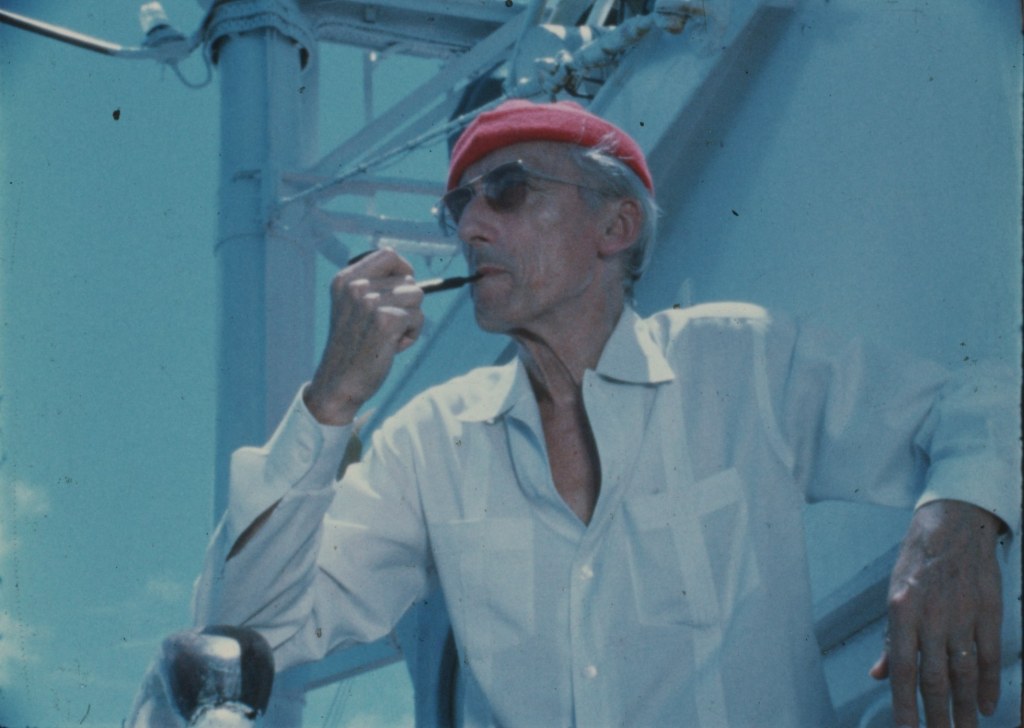

Thompson and his team climb to reach the next glacier.

With a combination of archival footage and contemporary interviews, the documentary explores Thompson’s career, which started with a years-long effort to access a mountaintop glacier located in a remote area of Peru. Though at first he was motivated solely by scientific curiosity, his discovery that glaciers around the world were shrinking eventually turned him into what he is today: a prominent cautionary voice in the fight against climate change.

Dramatic photography by cinematographer Devin Whetstone, accompanied by Paul Doucette and Jeff Russo’s equally dramatic score, set an appropriate tone for a film about a man engaged in a struggle for humanity’s survival. They help to make up for co-director O’Malley’s script, which sometimes fails to fill in salient details. Just what, for example, do Thompson and his colleagues do with the ice cores they work so hard to extract from glaciers? And what do these samples of ancient ice tell them about our planet?

But the film fills in just enough details when it reports on the rise of climate-change denial, a movement that caused politicians as diverse as Newt Gingrich, Sarah Palin and Mitt Romney to change from science supporters into science questioners. An eye-opening depiction of their transformation underscores the uphill battle Thompson and other activists face as they work to save humanity from its own excesses.

Rating: 3½ stars (out of 5)

Canary opens Sept. 15 in select theaters in New York and Los Angeles, as well as the Gateway Film Center in Columbus. Subsequent one-night screenings are planned Sept. 20 in multiple markets. For details, visit canary.oscilliscope.net.